Writen By Muravei-s

Translated from Russian by J.Hawk

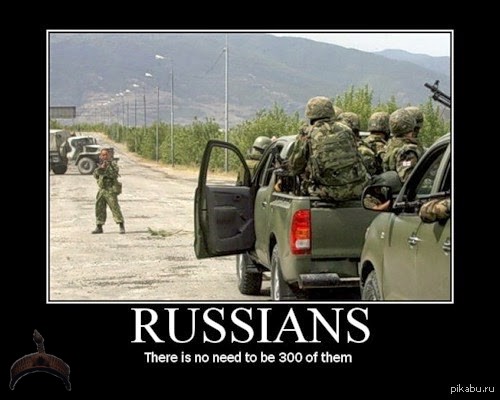

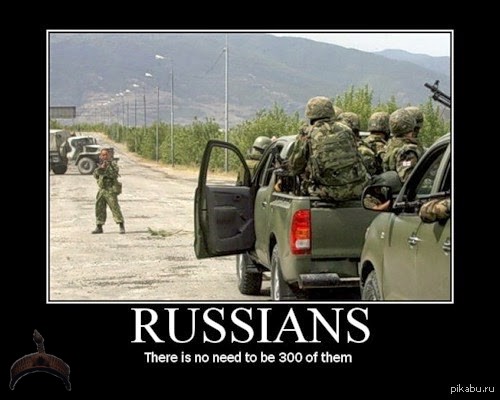

I was compelled to write this article by the following photograph:

It’s a famous photo. Georgia, August 8, 2008. After the Georgian army’s defeat, its retreating forces regrouped and decided to return to Gori, but encountered a Russian checkpoint.

One can see on the photo how a Russian Army soldier, with a machine gun slung over his shoulder, stands in the path of Georgia’s motorized infantry, whose officers threatened the machine-gunner in order to force him to let them pass, only to hear “go f*** yourselves” in response. Members of the media accompanying the column also tried to reason with the machine-gunner, only to receive the same response. In the end the column turned around and return to whence it came from. Foreign journalists later published an article with the title “You don’t need 300, one is enough.”

What was the soldier thinking? What did he feel at that moment? Was he not terrified? He probably was. Or maybe he was not hoping to have children and grandchildren, or to live a long happy life. Of course he hoped to.

Can you imagine a NATO soldier standing like that, with a machine-gun against an enemy column?

I can’t. They value their lives too much. So what makes us so? Why are we Russians different?

And why do foreigners consider us unpredictable madmen?

Photographs from other places visited by our soldiers flashed before my eyes. The Slatina airport, the famous forced march of our paratroopers into Pristina, to help our brothers, the Serbs.

200 Russian paratroops against NATO soldiers. What did they feel, standing face to face with superior opposing forces? I think they felt what our little soldier in Georgia did.

Donbass, Novorossia, 2014. Aleksandr Skriabin died as a hero, attacking a tank with grenades. He was 54 years old, he worked at the Talovsk coal mine as an equipment installer. He left behind a wife and two daughters.

Were his feelings really any different from those experienced by Aleksandr Matrosov, who covered the firing port of a German pillbox with his own body?

The core of the matter lies not in fearlessness, or indifference to what’s most valuable to us—our own lives. Then in what? I started to look for answers.

Is there another nation which loves life and everything related to it as desperately?

We live with open souls, with a hussar’s panache. We are the ones to invite Gypsies and bears to weddings. It is us who are able to spend the last of our money to throw a celebration, generously feed all the guests, and wake up the next morning without a penny to our names. We can live as if every day in our lives was the last. And there will be no tomorrow. There is only today.

All of our poems and songs are overflowing with love for life, but only we know how to listen to them and cry.

Only our people has sayings like: “If you want to fall in love, fall in love with a queen, if you want to steal, steal a million,” “who doesn’t risk, doesn’t drink Champagne.” It’s the desire to drink from the cup of life until it is empty, experience everything that can be experienced.

Then why do we, Russians, are able to part with life so easily when looking the enemy in the eye?

It’s laid down in our historical memory, starting with the time when the first aggressor set foot on our Russian soil. It has always been like that. Since the beginning of time.

Only the chainmail and the helmets are different, spears have been replaced by assault rifles. We have tanks and we have learned to fly. But the memory remains the same. And it is activated whenever someone wants to destroy or capture our home. The memory also bothers us when the weak are abused.

How does it work? Alarm bells inside of us start ringing, which only we can hear. The memory continues to ring until the uninvited guests are expelled from our land.

Then the most important thing happens. Inside each one of us a warrior awakens. Every one, from the meek to the powerful. This is what ties us with invisible threads. Foreigners will not understand it. You have to BE Russian, be BORN one.

When our land is in danger, or when somewhere on Earth someone is being harmed, be in in Angola, Vietnam, or Ossetia, our snipers become the most accurate and tankers—fireproof. Pilots become aces and recall such unlikely feats as ramming attacks and stall tactics. Our reconnaissance soldiers accomplish miracles, sailors become unsinkable, and infantry appears to be composed of stalwart lead soldiers.

And every Russian, without exception, becomes a defender. Even the oldest of men and the youngest of children. Recall the grandpa from Novorossia, who fed the enemy with a jar of honey filled with explosive. That’s a real story. We have a country full of such warriors.

Therefore anyone who expects to attack the Russians and to find them waiting on bent knees, welcoming the invaders with loaves of bread and flowers, will be sorely disappointed. They will see an entirely different picture. I don’t think they will like it.

They will see our grandfathers, fathers, husbands, and brothers. Behind them will be their mothers, wives, daughters. And behind them will be the heroes of Afghanistan and Chechnya, the soldiers of the Great Patriotic War and the First World War, the fighters from Kulikovo Field and the Battle on the Ice.

Because we are Russians…God is with us!

Respected aleksa_piter wrote the following remarkable words:

“Let’s look at Bubnov’s painting “The Morning on the Kulikovo Field.” Note the formation of the Russian regiments: the front rows consist of elders, behind them are the younger generations, the young, healthy, and strong warriors who represent the army’s main force. It’s an ancient, Scythian combat order, a brilliant conception from the psychological point of view. The first rows will be the first to perish when making contact with the enemy, one might say they are suicide warriors since they are wearing white shirts and have almost no armor. That’s where the saying “don’t get ahead of your dad on the way to hell” comes from.

The elders are supposed to die before the eyes of their grandsons, the fathers before the eyes of their sons, and their death will fill the hearts of the young with battle frenzy, adding the element of personal revenge. The word “revenge” [mest’] comes from the word “place” [mesto], it’s a purely military term describing the young warrior taking the place in the formation left vacant by the killed elder.”